How I write

Some practical tips

The novelist Steve Hely has a great line on writing:

Writing a novel— actually picking the words and filling in paragraphs— is a tremendous pain in the ass. Now that TV’s so good and the Internet is an endless forest of distraction, it’s damn near impossible. That should be taken into account when ranking the all-time greats. Somebody like Charles Dickens, for example, who had nothing better to do except eat mutton and attend public hangings, should get very little credit.

As a professional writer working in the age of the internet, I thoroughly agree. Obviously the internet is great for distributing my work, and for conducting research (you might have noticed that non-fiction books written before the internet age tend to have very sparse citations, some of them of the “this was once revealed to me in a dream” variety. Bless them, what other choice did they have?).

But the internet also rots one’s brain. It offers infinite distractions, of course, but an even more insidious problem is that constantly clicking between tabs, or between apps, also trains us to abandon trains of thoughts as soon as they become even slightly onerous. Sometimes the only way to think properly is to stare at a blank wall or a blank page for a long time, however much it hurts to do so.

I’ve been earning money as a writer for five years now, and before that I was a graduate student. During that time, I’ve developed some practical strategies for writing to a deadline which work for me, and which hopefully might work for some of you.

Here’s the TL;DR: you need to make the sticking points analogue.

By ‘sticking points’, I mean the difficult parts of the writing process. You’ll be searching for the right word, or wondering how to restructure an awkward section, and you’ll find that checking social media or the news is so much more attractive than surmounting this cognitive challenge. If you have access to the internet at these moments, the sticking points will be far more sticky, and you’ll end up in the procrastination self-hatred cycle that every writer I know (bar one!) is familiar with.

Writers tend to be neurotics, so these negative feelings will inevitably descend sometimes. To quote another novelist on the writing process, this time the multi-award winning author Francis Spufford:

When it’s going badly, then you feel it: there’s the gluey fumbling of the attempts to gain traction on the empty screen, there’s the misshapen awkwardness of each try at a sentence (as if you’d been equipped with a random set of pieces from different jigsaws). After a time, there’s the tetchy pacing about, the increasingly bilious nibbling, the simultaneous antsiness and flatness as the failure of the day sinks in. After a long time - two or three or four or five days of failure - there’s the deepening sense of being a fraud. Not only can you not write bearably now; you probably never could. Trips to bookshops become orgies of self-reproach and humiliation. Look at everybody else’s fluency. Look at the rivers of adequate prose that flow out of them. It’s obvious that you don’t belong in the company of these real writers, who write so many books, and oh such long ones. Last, there’s the depressive inertia that flows out of sustained failure at the keyboard, and infects the rest of life with grey minimalism.

Uh oh, even Spufford feels like shit sometimes.

Still, there are some ways around the dreaded “failure of the day.” And the strategies I’m going to describe here all relate to managing one’s relationship with the internet.

As an aside, I make no comment on writing schedule. Nowadays I spend two or three working days a week writing, and my aim is to produce 1500-2000 high quality (i.e. publishable) words a week – not as much as I’d like, but then I am a working mother so my time is really stretched. I used to work late at night, most nights, but that’s no longer practical with a young child. Just do what works for you, ideally writing at the time of day when you’re most alert. I agree with the standard advice to write regularly, not only when inspiration strikes. But, if the spirit of inspiration is moving through you, definitely keep going! I once wrote the first draft of an essay on my phone while sitting on the kitchen floor, because an idea sprang to mind.

The point I really want to emphasise here is not concerned with scheduling, but rather with the power of going analogue. For me, that means:

1. Writing longhand.

2. Reading on devices that are not internet enabled.

3. Reading on paper, whether books or print-outs.

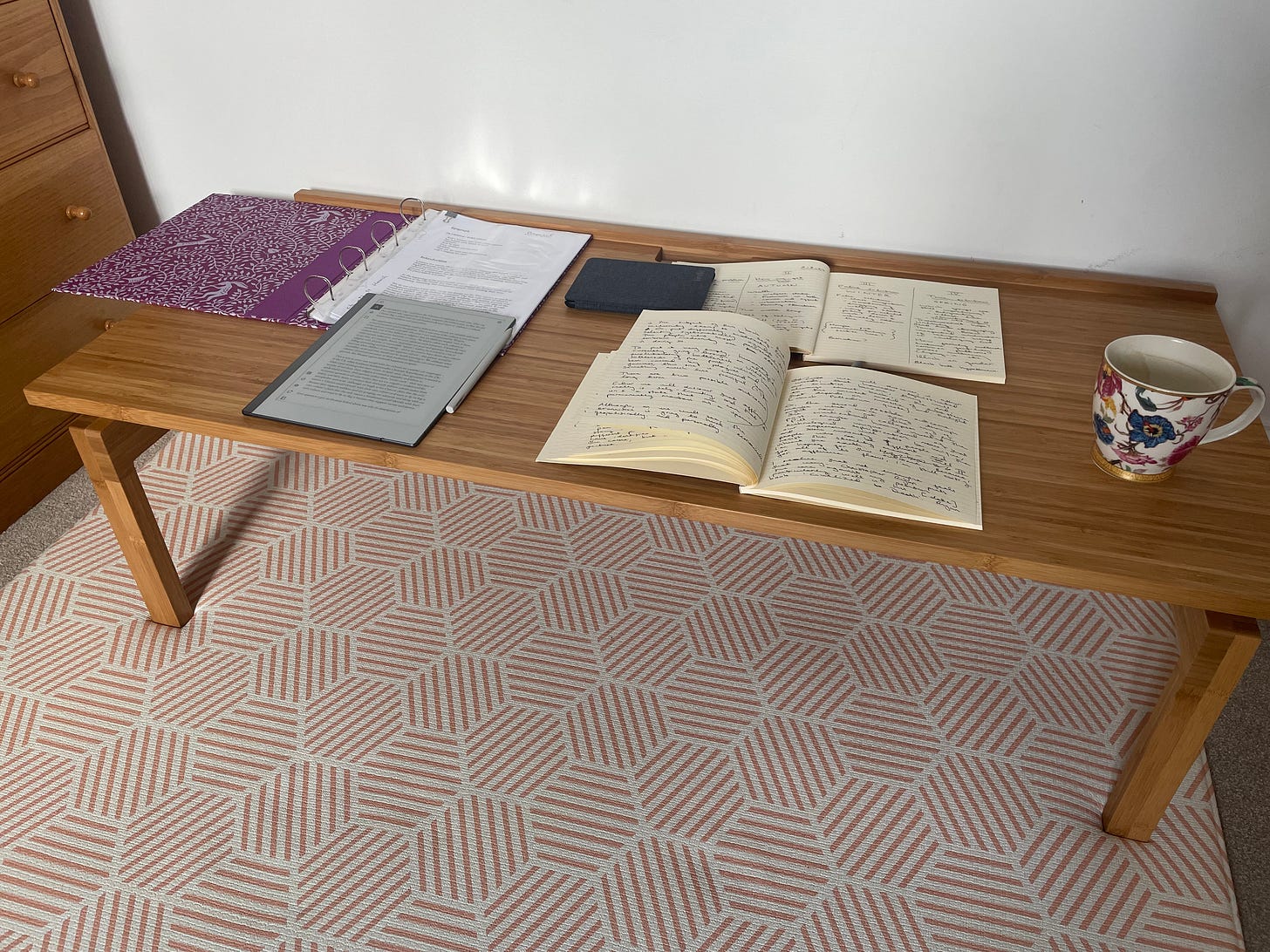

Here’s what my desk looked like yesterday when I was working on my next book:

What you can see here is the ring binder, plus two notebooks, that I’m using to draft part one (all from Cambridge Imprint Pattern Makers); the reMarkable tablet I use to read PDFs; and my Kindle. The folding desk is from a nice little company called Floor Desk. We don’t have enough space in our house for me to have a dedicated work space, so I store the desk under my son’s cot and sit on his playmat while I write (I find it more comfortable to sit on the floor for some reason).

A note on the reMarkable: I bought it early last year in the hope of using their handwriting function. The idea is that you write longhand on the screen, which is designed to feel like paper, and then the reMarkable will translate your handwriting into text which you can email to yourself. I’ve never managed to get that function to work properly for me (maybe my handwriting is too illegible?). But I like it anyway because there’s a handy browser extension that allows you to save web pages as PDFs which are then automatically sent to the reMarkable.

I’ve experimented with using a typewriter, having bought one a few years ago from Mr and Mrs Vintage Typewriters. It’s quite fun, and can be good for first drafts. But I find adjusting to the heaviness of the keys difficult when I’m used to using a Mac. It works for some writers, though, so worth a mention.

(None of these companies are sponsoring me, by the way. I just like their products).

My standard writing sequence goes like this:

1. Plan/spider diagram/stream of consciousness longhand.

2. More substantial longhand draft, using the second notebook so that I can more easily refer to the plan.

3. Sometimes a second longhand draft, written in the first notebook.

4. Type up the draft (editing as I go) and print it out, double spaced.

5. Edit the print-out longhand.

6. Type up the edited version.

This works just as well for 600 word op-eds as it does for books, although of course the books need to be written in small-ish chunks. On a fresh workday, it’s good to start at stage 4. That way, you revisit what you wrote on the previous day and get into the flow of the argument before you start editing or composing new words. This is apparently what Joan Didion used to do: she’d retype from the very beginning of the chapter before adding anything to it.

Alongside all this, I read from books/the reMarkable/the Kindle as much as possible, and I avoid internet ‘research’. It’s so tempting to think “oh I’ll just go check that one detail” but, next thing you know, you’ve wasted an hour on the internet. So if I don’t know something that needs checking online, I’ll put it in square brackets: “[date]”, “[who said this?]” etc. And then will do all of those pick-ups in one go later on. Pick-ups and typing up aren’t sticky tasks, so it’s safe to do them on the laptop.

In terms of word processing software, I’ve been using Scrivener for almost a decade now, and will only ever use Microsoft Word when I need to send a finished piece to an editor. Here’s what the Scrivener document for The Case For Having Kids looks like right now:

The great thing about Scrivener is that it allows you to collect your plans, drafts, notes, and research resources into one place and easily toggle between them, including using a split screen. You can even download web pages which are then archived within Scrivener.

Sometimes, of course, you do need to use an internet-enabled device. In terms of my digital guardrails, I do the following:

1. A 20 minute daily limit for Twitter (I can override the limit, but doing so is annoying).

2. No email app on my phone.

3. No browser app on my phone home screen, so I can only access the browser through an annoying work-around.

4. Definitely no Twitter app on my phone (are you mad???).

I usually have my phone on loud in the room while I’m working, in case there’s a childcare emergency, but I keep it out of arm’s reach. And I keep my laptop in another room when I’m working analogue.

Here endeth the lesson. This is all a work in progress – hopefully in a decade I’ll have refined this process, and in two decades I’ll have refined it even further. But I reckon I’ve published at least a quarter of a million words by now, often written through the fog of self-hatred and procrastination, so there are some hard earned lessons in here that will hopefully be useful to someone somewhere.

Very good. One further suggestion: I've only ever got anything done by giving myself permission to fail.

I write on my phone too! I drafted my first 2 books on mobile Google Docs, mostly when I was supposed to be doing something else.

I love the tea in the photo. Your setup looks so proper and British.