Immigration is not the answer to low birth rates

A guest post by Tom Jones

Hi everyone – as some of you will know, I’ve been travelling with my family for the last month. We were mostly in Australia, where the Centre for Independent Studies invited me to give a talk on reactionary feminism.

Normal MMM service will resume next week. In the meantime, I’m very pleased to offer this guest post from friend of the pod Tom Jones, a.k.a. The Potemkin Village Idiot.

What’s the solution to Britain’s fertility crisis?

There are, broadly, three schools of thought. One – which it’s reasonable to assume many subscribers of this Substack and the nation of Hungary adhere to - is that you can, through carefully structured incentives and social changes, encourage birth rates to rise to replacement levels.

One, to which I and the People’s Republic of China subscribe, is that the ageing population is, given the potential for automation, robotics and AI, actually not *that* much of an issue. This house believes domestic birth rates can and should be raised, but that growth by increases in productivity, not population, is the solution.

The final school of thought is that nothing can be done about the Western fertility crisis, and that the only solution is to supplement the working age-population with immigration. This, sadly, is the school which currently governs Great Britain.

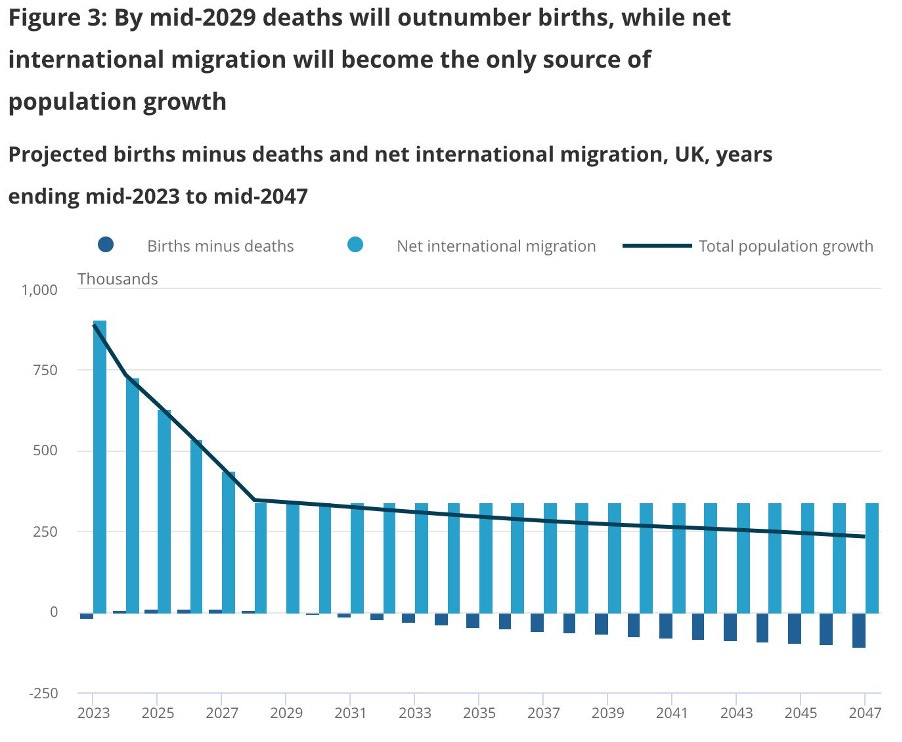

The latest national population projections from the Office of National Statistics indicate that net migration will be the sole driver of population growth in the UK over the next 25 years. Between mid-2022 and mid-2047, the number of deaths is expected to exceed births by 1.1 million. Despite this natural population decline, the total population is projected to grow by 8.9 million, driven by an estimated net migration of 10.0 million during this period.

The ONS projections also emphasize the challenges posed by Britain’s ageing population, with pensioners being the fastest-growing age group. But even after a quarter-century of world historical levels of net migration have had minimal impact on improving the long-term outlook.

The reality of using immigration to ‘fix’ the working age population is simply staggering.

In 2000, the Population Division of the Department of Economic and Social Affairs at the United Nations Secretariat modelled two scenarios in which the UK utilised immigration to address the dependency ratio. Scenario IV, which kept the age group between 15-64 years constant at its maximum of 38.9 million from 2010 on, required 6.2 million immigrants between 2010-2050, at which date 13.6% of the population would be post-1995 migrants or their descendants. Scenario V, which kept the potential support ratio at its 1995 level of 4.09, required 59.8 million (a little over a million a year) migrants between 1995-2050, at which date 59% of the population would be post-1995 migrants or their descendants. More recent estimates have suggested this policy will result in Britain becoming 40% foreign born in just 26 years.

As shocking as this is, it may not even fully underline how insane this policy is. That’s because it’s possible that immigration is actually suppressing native birthrates.

Whilst immigrants may increase the birth rate – for the first generation at least – the sheer scale of immigration requires massively increases spatial competition for housing. This, naturally, means higher costs.

It’s clear that Britain was suffering a housing shortage before mass migration. Research from the Centre For Cities found that, “had the UK built houses at the rate of the average Western European country from 1955 to 2015, it would have added a further 4.3 million homes than it actually did”.

As the paper notes, “there were already housing supply issues in the UK before the shift towards net immigration in the 1980s and 1990s.” But the sheer weight of numbers, combined with Britain’s historic housing deficit and inelastic supply, has turned a shortage into a crisis. According to the Centre for Policy Studies, the unprecedented levels of migration over the last decade mean 89% of the cumulative net additional dwellings deficit in England between 2013-2023 was generated by net migration. Government research showed that between 1991-2016, ‘the increase in the non-UK born population in England is expected to have led to a 21 per cent increase in house prices; holding all else equal.’

These artificially increased housing costs are causing couples to defer starting families for longer and longer. The authors of ‘The Housing Theory of Everything’ note with extreme simplicity that; ‘the more expensive an extra bedroom is, the more expensive it is to have more (or any) children.’ One study found a 10% increase in house prices caused a net 1.3% fall in birth rates. Another, from the Adam Smith Institute, found that the rising cost of housing between 1966-2014 (broadly coinciding with the development of mass migration) prevented 157,000 children being born.

There is a paradox here; if increased housing costs are making people poorer, shouldn’t we be seeing a boost in fertility? TFR is highest in poorer countries, and we have become low fertility at exactly the same time that we have become richer as a nation. If income is declining, shouldn’t fertility be increasing?

That’s because perceived wealth is more important than actual – an idea known as the Easterlin Hypothesis. In the 1960s, economist Richard Easterlin proposed that individuals' fertility decisions are influenced by their income relative to their material aspirations and their socioeconomic background.

Young couples, he argues, strive to achieve a standard of living at least equal to what they had growing up—a concept known as relative status. When individuals feel their income meets or exceeds these aspirations, they are more likely to have more children. Conversely, if they feel their income falls short, they may delay marriage and have fewer children. Data backs this up; a paper on ‘Disentangling wealth effects on fertility in 64 low- and middle-income countries’ showed that relative wealth had a consistent negative effect on fertility, while absolute wealth had a weaker positive effect. That en-masse immigration works to decrease GDP per capita is doubtless exacerbating this process even further.

Housing costs may also be playing a role in the fertility convergence of migrants, too. Migration settlement patterns mean the effect of migration on housing is particularly acute in London and the South East, which is home to a disproportionately high number of migrants – and where the biggest housing shortages are primarily concentrated. By coincidence, whilst the TFR for non-UK-born women is higher than UK born women, that is not the full picture; fertility of non-UK-born women has been in long-term decline and in 2021 stood at 2.03, below the TFR replacement rate of 2.1. In fact, the TFR rate of non-UK-born women has not reached above 2.1 for a decade.

The compounding effect of the rising age of first-time mothers means we may not have seen the worst yet; the average age of a first-time mother is now 30.9, the highest on record. Given trends, there is little reason to predict that won’t continue to increase. Given 30 is the age at which female fertility begins to decline, this carries huge potential problems; female fertility suffers a drop at 35 which, when the average age gap between first and second babies is three years and eight months, is dangerously close to when families should be having a second child. Britain’s fertility problem may get much, much worse before the decade is out.

No one who is sincere about solving the fertility crisis, or who has thought about it for more than five minutes, will argue there is a single solution to it all. But whether you follow a more technological solution to our ageing population, as I do, or a birthrate-first approach, as Louise might, it’s common consensus that lowering the cost of having children is an easy win for raising birth rates. All the evidence points to the fact that laissez-faire, en-masse immigration is a terrible idea, including for birthrates. Regardless, it’s still being pursued – largely, I would argue, because it’s the easiest possible solution to many of the crises our politicians face, even if it exacerbates them in the long run. I guess, once you’ve jumped off a cliff, your only hope for survival is the abolition of gravity.

Read more of Tom’s writing at The Potemkin Village Idiot.

I’ve always enjoyed Tom Jones’ singing (It’s not Unusual and Sexbomb being a couple of my favorites), but I had no idea he was such an astute writer on demographics…..apologies, I’m sure the esteemed Mr Jones receives versions of that lame joke often

We need more of this pointing out the obvious that this is a longterm disaster to those who it is not so obvious to. On my more positive days I figure the government is like me and has mostly inly been exposed to the more educated of the world and doesn’t understand what they are doing. “That nice Pakistani doctor neighbor of mine is such a nice chap, what’s the problem here?” On my more negative days I figure the upper classes despise the lower classes and don’t care what the future looks like after they are dead. In this view, the UK is the British empire, only the local English are the natives to be managed now

I listened to your interview in Australia. One quick note: while I agree with everything you said about Tate, I’d also argue that he is an easy way for boys socialized into “acting black” to do so. He’s culturally similar to the dominant strain of black American culture, and in a perverse twist on being a more open society and shedding ourselves of any racism, most white, Asian, and Hispanic boys now act as black as they can get away with. Tate is a role model for that cultural trend as much as a product of the Internet and the feminization of institutions. White and Asian boys in the Anglosphere are desperate for same culture role models; there are notably fewer now in popular sports and movies. The fatherlessness trend obviously makes this a hundred times worse.