Why Men Love Ken

On Barbie, masculinity, and modernity

NB: I’m going to be publishing occasional Substack essays – both free and paywalled – alongside the MMM podcast: weekly bonus episodes for founding members plus weekly or bi-weekly interviews. I’ve now started work on my next book, The Case For Having Kids, and will be using these essays as a drawing board, to work through ideas and elicit feedback. Plus sometimes – as in this case – I just have a thought I want to get down on paper.

The Barbie film probably deserves a book-length treatment. Given the number of think pieces, memes, and 43 minute Ben Shapiro monologues it has so far generated, I suspect it will receive one before long. But I have just one thought to add here, having spent a week ruminating on the Barbie vision of sexual politics. It’s about Ken.

There was an essay titled Why Men Love War published in Esquire magazine in 1984. The writer was William Broyles Jr., a screenwriter and veteran of the Vietnam War. I urge you to read this classic essay if you haven’t already done so, particularly if you are a woman, because it offers an insight into the young male mind that will seem strange to many female readers – even alienating. That was certainly my experience of it.

Broyles writes:

War is ugly, horrible, evil, and it is reasonable for men to hate all that. But I believe that most men who have been to war would have to admit, if they are honest, that somewhere inside themselves they loved it too, loved it as much as anything that has happened to them before or since.

He lists a bunch of reasons why men might love war: a temporary feeling of comradeship, relief from loneliness, certainty about your social role, the thrill of evading death. All of these I can understand and empathise with, at least in part. But then he goes on:

[T]hese are the easy reasons, the first circle, the ones we can talk about without risk of disapproval, without plunging too far into the truth or ourselves. But there are other, more troubling reasons why men love war. The love of war stems from the union, deep in the core of our being, between sex and destruction, beauty and horror, love and death. War may be the only way in which most men touch the mythic domains in our soul… It is like lifting off the corner of the universe and looking at what's underneath. To see war is to see into the dark heart of things, that no-man's-land between life and death, or even beyond.

Broyles describes standing with a colonel and looking together at the terrible aftermath of a skirmish:

[T]here was a look of beatific contentment on the colonel's face that I had not seen except in charismatic churches. It was the look of a person transported into ecstasy.

And I—what did I do, confronted with this beastly scene? I smiled back, as filled with bliss as he was. That was another of the times I stood on the edge of my humanity, looked into the pit, and loved what I saw there. I had surrendered to an aesthetic that was divorced from that crucial quality of empathy that lets us feel the sufferings of others. And I saw a terrible beauty there. War is not simply the spirit of ugliness, although it is certainly that, the devil's work. But to give the devil his due, it is also an affair of great and seductive beauty.

I simply cannot imagine loving such a scene. Not at all. Not even slightly. Broyles’ description of his pull towards violence is completely foreign to me.

And I have exactly the same response when men speak and write honestly about the extremes of male sexuality. This weekend, we’ll be releasing my interview with Niccolo Soldo on the early history of HIV/AIDS in the United States – a history that is often misremembered, in part (I’d argue) because so many women are ignorant about the reality of male sexuality, including gay sexuality. As I mentioned during this episode, there’s a line from an interview with Russell T. Davies that my ladybrain finds confusing. Davies is discussing his dramatisation of 1980s gay life in the TV series It’s A Sin, and he recalls of his own youthful sex drive:

How horny are you at 17? You’d have sex with a letterbox.

No, actually, I wouldn’t have had sex with a letterbox! At the age of 17, or indeed at any other age!That desire is not familiar to me, and nor – I think? – is it familiar to other women, perhaps with a handful of exceptions. Testosterone is a helluva drug, and its effects on the male psyche during the crucial 15 to 30 age range are hard for women to understand. Its effects are also, I suspect, underplayed in mixed company, since most men intuit (correctly) that women would be repulsed by the truth. The writer who goes by the pseudonym Delicious Tacos is one of the few men who is flagrantly honest about the extraordinary intensity of his sex drive (he likens the male libido to the pain of a mother watching her baby be crushed under the wheels of a truck). It’s for precisely this reason that I find his work unreadable – it’s just too weird and gross.

Which brings us back to poor old Ken. In this week’s bonus episode, my husband and I discussed the Barbie film in relation to older films about the impact of affluence on modern men: Fight Club, Office Space, American Beauty, The Matrix, etc. These are all films about men seeking out stimulation because they are bored by the safety and comfort of 1990s-2000s America. Office Space, for instance, ends with our emasculated male protagonist finding meaning by leaving his bourgeois office job and becoming a construction worker, while the hero of the Matrix finds romantic love, friendship, and satisfaction only through privation and peril (speaking of, there’s a good and funny Matrix reference in the Barbie film, when Barbie tries her darnedest to choose the blue pill).

Barbie offers a more intensely dystopian iteration of this genre, because the plight of Ken is so much worse than the plight of the men in these older films. Forget ennui, there is zero role for the men of Barbieland: there is no work to be done, no problems to be solved, no protection to be offered, no children to be conceived and fathered. Ken’s six pack is useless, since his society has no need for either physical strength or sexual attraction, given that his smooth plastic crotch precludes the possibility of sex. Ken has no political power, no property rights, and – worst of all – no telos. Ken is completely expendable. And, before his introduction to the real world, he’s too brainwashed to understand the true cause of his dissatisfaction.

And here’s the really painful bit, for those who’ve spotted the parallels between Ken’s expendability and the expendability of the twenty-first century man: it’s not feminism that cucked Ken, it’s modernity.

We Westerners live in the safest and most comfortable period in human history, and this material fact has had a profound effect on gender relations (as Mary Harrington so brilliantly describes in Feminism Against Progress). Phyllis Schlafly was right to observe that the washing machine did more to liberate women than the feminist movement did. Which is to say, the enormous technological changes that followed the industrial revolution, and accelerated in the twentieth century, allowed women to participate en masse in both the labour market and public life because it became much quicker and easier to keep a household warm, clothed, and fed.

Unless you decide to do things the hard way – cooking from scratch, scrubbing your front step, whatever – you can now perform the bare minimum tasks of the housewife in the time it takes for your microwave to ping. Women continue to experience the double shift, not primarily because of the work of cooking and cleaning, but instead because of childcare and (to a lesser extent) elder care, which remains primarily women’s work, and is enormously time consuming, hence why it is so often outsourced – again, to women.

Care robots have so far turned out to be useless, both because people don’t like them, and also because they can’t even perform physical care very well. So childcare and elder care must still be done by humans, and the vast majority of those humans will be female. The idea that we would ever employ 50/50 men and women in these roles is laughable, absent some kind of state coercion, since the parents and adult children who pay the care bills judge women to be both more instinctively caring and less likely to sexually abuse the vulnerable people in their care (accurately, all stereotypes are at least partially true!)

In other words, low skilled feminine work has survived technological change in a way that low skilled masculine work has not. And while drudge work is often shitty, it is psychologically far preferable to having no work to do at all.

We’ll all be familiar with the disappearance (or exportation) of male jobs over the last century or so, from coal mining to heavy manufacturing. But think too of the domestic tasks that men would once have performed on a daily basis: collecting and preparing firewood, protecting the family and property from both animal and human attack, doing heavy labour around the home. Some of those tasks are now performed by machines (e.g. heating the home), while others are performed by the state (e.g. policing), and modern men are left with a handful of ‘macho’ domestic tasks that require some degree of either masculine-coded expertise (e.g. car maintenance) or physical strength (e.g. mowing the lawn).

Do you remember when then-PM Theresa May discussed her husband Philip’s domestic work around their home? “I take the bins out” was his (much derided) contribution – a classic modern male chore, transporting a slightly heavy object to the kerb, where it will be collected by men employed in one of the few jobs that still demands male strength (although the automation of bin collection is well on its way).

Men continue to dominate elite professions that demand traits more commonly found in men, including risk tolerance, competitiveness, and extremely high non-verbal IQ. And these elite men can find satisfaction through macho extra-curricular activities like Crossfit and Second World War podcasts. They’re doing ok.

But non-elite men are not doing nearly so well, as writers including Richard Reeves, Warren Farrell, and Caitlin Moran (!) have all recently outlined, since the uniquely masculine contributions they have to offer to the family and to the state are now far less valuable than they once were (as Ken sings, “anywhere else I’d be a ten!”)

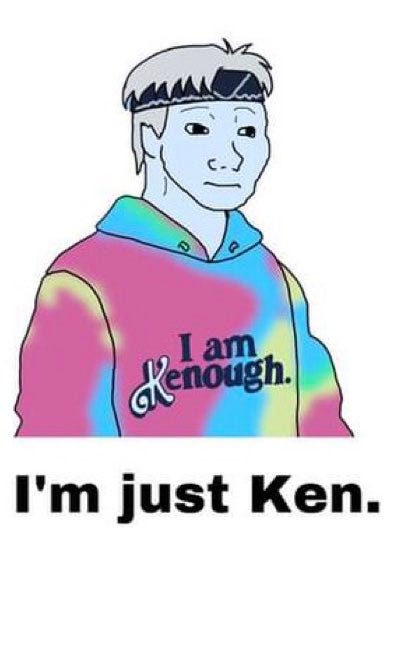

In one of the many moments of incoherence in the Barbie film (what on earth does Greta Gerwig think ‘patriarchy’ is???), Ken tries to find employment in the real world, having falsely assumed that being a man would give him access to any profession of his choice. But he soon finds that he cannot get a job as a doctor, a businessman, or a lifeguard. The promised ‘patriarchy’ does not have much to offer unskilled men, as it turns out. Ken is as expendable in the real world as he is in Barbieland. He is not kenough.

And all this is played for laughs, because Greta Gerwig & co. consider masculinity to be either bad – think of the sexual harassment that Barbie experiences in the real world – or ridiculous, as in Ken’s LARP-y attempts to become a beer-swigging cowboy.

Reactionary Feminism diverges from other forms of feminism – including Barbie feminism – in that it takes masculinity seriously, having started from the recognition that men and women are profoundly different in important ways. If we believe – wrongly, insanely! – that all differences between men and women are the product of socialisation, then the best advice we can offer to unhappy Kens is that they ought to become more like women. Go to therapy. Cultivate their soft skills. Get over themselves.

Maybe that would work in Barbieland. But here in the real world, we still have to contend with the masculine energy that William Broyles Jr. describes so well – an energy that can be channelled in both extraordinarily antisocial and extraordinarily prosocial directions, depending on the incentives at play.

Great post. This week, Danica Patrick (one of the few female race car drivers) said women will always be underrepresented in racing because it requires a level of aggression and risk-taking that doesn't come naturally to most women. Now she's getting a lot of negative press for being sexist and having "internalized misogyny." Jalopnik said DP should have called it "competitive" rather than "masculine." I almost can't believe they're being serious.

DP's scandalous comments:

"And at the end of the day, I think that the nature of the sport is masculine. It’s aggressive. You have to, you know, handle the car — not only just the car, because that’s a skill, but the mindset that it takes to be really good is something that’s not normal in a feminine mind, in a female mind. You have to be, like, for me, I know if somebody tries to bow up or make it difficult on me, I would go into like an aggressive kill mode, right? You just want to go after them, and that’s just not a natural feminine thought. I say that because I’ve asked my friends about it, and they’re like, “Yeah, that’s not how I think.” https://www.boundingintosports.com/2023/07/former-nascar-driver-danica-patrick-accused-of-internalized-misogyny-after-calling-racing-a-masculine-sport/

Oh my gosh I had a neighbour that actually did have sex with his letterbox in full public view